As now-retired medical first responders, Randy and I certainly considered how we would handle health issues and crises while sailing on the Odyssey long before we left Colorado. I frankly don’t fret about that kind of thing much because I’m healthy and lucky. But it would be foolish to depend on that.

It’s important for retired Americans to know that Medicare does not provide coverage outside the U.S. We absolutely did buy health insurance that would cover us everywhere except the U.S., but the details on that will have to wait for a future article. We’ll try to get that done soon.

So while we were careful with arranging insurance for us, we weren’t stressed about our health. But we noticed some other Residents were and are: life happens no matter how you choose to live your life. Anyone can face a medical situation that needs attention any time, anywhere. And in several cases, it already has.

The Medical Center Has Been Busy

The people who were anxious were right to be: Residents started getting hurt right away. And then some illnesses surfaced. My reaction was “stuff like that happens in life, no big deal.” But, it increasingly became a big deal, even when you have a medical center onboard. Falls were the first noticeable issue. We decided the first insurance policy we got was inadequate, and switched plans, getting considerably better coverage for year 2. (Year 1 started when we left the U.S. in early 2024, and included our months in Belfast. Year 2 happened to start when we left the U.S. again — after the Hawaii-Alaska segment.)

Basic illnesses and accidents can be taken care of readily by the onboard medical team, which includes a doctor with Emergency Room experience, and two nurses. They do have the ability to do some lab work (blood and urine tests), and X-rays.

Serious situations may need more resources and professionals than we have. When one of the staff had a heart attack off the coast of Brazil, we were under the impression that a helicopter would come out to get the patient. The reason we heard that it wouldn’t/couldn’t come was because Rio’s annual Carnival was in full swing. We translated that to they needed the chopper to be available for potential emergencies in Rio.

The next time we had an emergency while at sea and a helicopter might have helped, there was some other reason that evacuation was not available. Lesson learned: essentially, we cannot rely on helicopters for transport even if the emergency is life and death.

For both of those events, the Captain pushed the ship to get to the next port quickly, which was still several hours away. The Golden Hour Of Care we learned about in EMT classes was out of the question.

The first time, in Rio, port officials sent a speedboat to meet us to offload the patient because there was no place for us to dock. In the second case, when we arrived in the wee hours of the morning, we learned that particular port isn’t staffed around the clock, and we would have to wait until morning to get the Resident to care. Once we got finally tied up at the pier, we again were stopped by the lack of immigration personnel to process the ailing person. What lessons we are learning!

O’s Are Good

I learned in EMT school that “O’s are good” — we all need oxygen, and the first thing to check on a patient is their airway and breathing. I’ve experienced not breathing well during travel, including bronchitis in Tibet at 12,000 feet elevation. Here, we have had several (too many!) examples of respiratory issues on the ship, including at least three pneumonia cases. All three were significant enough that the Residents were hospitalized onshore. They “couldn’t” come back until their blood oxygen levels were high enough to come home.

One of those was hospitalized for a week and found her way back to the ship through a series of transportation devices across several islands. Another only stayed overnight and made her way back just before we departed that port. A couple of Residents, not acute pneumonia cases, decided they couldn’t live onboard because allergy issues were too much for them.

One never plans on having a stroke; they happen anyway. Do you have the insurance to help you get home, or to be hospitalized wherever you are?

The seriousness of the stroke will dictate some of the location of care and recovery. A severe stroke led to that second dash to land, and that Resident made it to the hospital, but died there. In a way, it was a relief in that their death wasn’t due to any delay in treatment: they wouldn’t have survived even if it happened in a big city with great hospitals.

Lesson Learned

As we watched these various emergencies unfold, one thing stood out to several of us beyond the “mere” medical treatment aspect: In addition to the medical care, what about companionship and assistance getting to and from the hospital? A friend at your side can make all the difference between a miserable experience and a tolerable — even excellent — one.

It’s something that doesn’t just happen: it needs to be planned for. If you’re hauled off to a hospital in a country where you don’t know much about the culture, and don’t speak the language, your survival could depend on having someone helping you navigate the treatment plan. Will someone, for instance, know what your regular medications are, and can they get into your cabin and pick up some things (and meds)? Probably not …if you don’t set that up in advance.

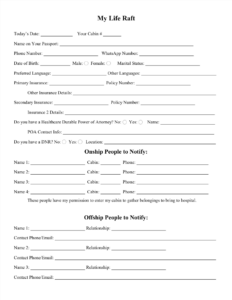

So a group of Residents didn’t merely plan for it, we brainstormed what should be included on an informational form, and where it should be placed to keep it private until needed so that it could be easily found. Once the group had the form outlined, Randy then whipped it up in software so that it could be distributed in PDF format, and it’s dual purpose: the PDF itself can be filled out on a computer (with the right free software), and saved so it can be updated later. OR it can be printed out and completed by hand, and copied as needed.

I called it “Your Life Raft”. It doesn’t replace insurance, research, or your own history knowledge. It aids you having everything gathered together that a hospital might need to get going on treating you. Part of the Life Raft is to have Buddies identified who will assist you in any number of ways. I hope I never need my Life Raft Buddies, but I have my form and Buddies all ready to go should that need arise.

As with pretty much every topic this entire site discusses, it all comes down to one thing: Doing your homework.

Originally Published December 13, 2025 — Last Updated December 14, 2025

Hi! I had been on 3 cruises so far. I *always* buy insurance when I make reservations on the ship. Never know what’ll happen!

Good idea on that “My Life Raft”.

Keep on cruisin’!!

—

Yes, insurance is a must. The problem is, you don’t want “travel insurance” for a super-long cruise. That’s why it will take a carefully considered full article to explain, which we’re working on. -rc

I’d also be interested in understanding how expats navigate US Medicare Parts A, B, C, D. Unless you’re docked where you can use US services, you’re being required to pay for insurance you may not be able to use.

—

That will be covered in our insurance article. -rc

My quick reply, to hold you until the Insurance Article is posted, is that many fly home to tend to medical things. Depending on where we are, that could be an expensive trip. How serious your medical need is could negate the wisdom of traveling for your medical appointment.

I chose to continue with my Medicare coverage so that I could have it when I wanted it. I don’t want to be without it.

I eagerly look forward to the Insurance Article. But I do find a certain irony of Americans (of all ages) lacking in insurance travelling abroad for affordable health care, and retired Americans living abroad travelling back to the States to use Medicare. I wish I had more to add here, and especially a solution, but all I have is that little dose of irony.

—

You’re not wrong! But yes, I expect it to be an interesting and eye-opening article. But as you also probably suspect, it’ll be a little difficult to write it clearly, so that’s why I’m not making any promises as to exactly when it will be published. -rc

Rick and I have a very good insurance — SkyMed — that will get you home from almost anywhere in the world. We haven’t needed it — yet — but friends in our travel group used it just last summer.

—

If someone thinks medical helicopters are expensive (and they are: $15,000-$50,000 is probably typical in the U.S.), think about a medical jet flying half-way around the world to pick them up and fly them home with a doctor and a nurse or two! There are multiple such companies providing such coverage, so it’s wise to shop around and, of course, read all the fine print before buying. -rc

I believe Skymed only covers you in the US, Canada, and Mexico. I too have Skymed and thought that it would cover me. Please check it out before you travel to any other country.

—

AKA, “it’s wise to shop around and, of course, read all the fine print before buying.” 🙂 But yes, a primary factor to check FIRST. -rc

Hi Kit, this is my hospital info, I’m in UK but it can be modified for anywhere. When I go into hospital nurses are so pleased that I have all my drug names/dosages and times of administration. It saves them so much time. I have copies with me, in my car, in a small hospital bag and in my home hospital bag. It was saved as a word doc, if you want a copy of the file just give me a contact email and I will send you one. Have fun with your cruising, something I cannot consider due to multiple health issues. LOL.

—

The form didn’t come through well at all, but it includes name/address/date of birth, doctor info, medical/surgical history, medication details, allergies, next of kin, etc. YES this all saves nurses lots of time on hospital admission! But it also speaks for you when unconscious so doctors can start getting some clues as to why you might be unconscious (diabetic? Check blood sugar, stat!) Etc. This is exactly the sort of information that’s on the form we created, and more, with some of the more being specific to our situation so that it also guides ship personnel and our onboard friends. -rc

I’ve lived in Portugal for nearly 9 years, and when I hit Medicare age, I simply did not take it. We have socialized medicine here, and I have a supplemental private health policy. I have no need for A, B, C, or D. No entity ever said I was required to pay for that.

That was most interesting. As a landlubber in Kansas, my first thought was perhaps that form or something similar would be good for all of us to help prepare.

—

It absolutely is, and indeed Your Life Raft is partially based on something U.S. medics look for in homes: any sign of something similar to the Vial of Life, which wasn’t fully practical because it was too small (the “Vial” being an old pill bottle). What we handed out later was a magnetic red plastic envelope with forms to fill out that would be helpful to medics and Emergency Room staff. The magnet is for sticking it to the fridge or other conspicuous place.

The problem I always had with it is information changes (e.g., medications come and go), and it’s such a pain to fill out the entire form again and again, it tended to be 1-10 years out of date when we did find them. That’s why I wanted an easy-fill PDF (and we recommend several free PDF form-fillers) so that it can be saved and then simply updated when needed, not all filled out again. Best bet: call your local EMS agency’s non-emergency number to ask what medics in your area look for, and get that. They may even drop off forms and such an envelope for you and each family member. -rc

And do take action on filling out the form. A blank form is no better than no form at all. I only know of 3 people on the ship who have filled out the form. There may be others, but I haven’t checked. I’ll do that soon.

—

So you, me, and only one other?! 😮 -rc

Do you have any URLs for some pre-existing such forms? Or even just a sample set of info. that should be on the form? I have the s/w to make & maintain my own form but I’m worried I’d exclude something I really should include or include extraneous stuff.

—

You can download the PDF “original” Vial of Life form from their web site for free, with the sad irony being it’s not a fillable PDF. I think you can register there and fill it out online, but then there are privacy risks. -rc

Does the company have a dedicated port agent at your stops? On my much shorter cruises with the moms that was the first name and contact info I got before leaving the ship.

—

Pretty much every ship works with the Port Agent, since that’s the way we get dock space, or even anchorage reservations. Also, should someone get left behind because they weren’t back on time, the ship hands the affected passenger’s passport to the Port Agent so the passenger can do what’s needed to rejoin the ship, which usually means some kind of travel (at their own expense). In 14+ months, I’ve not heard of anyone being left behind — or, for that matter, needing to contact the port agent for anything beyond relaying a package. -rc

Love the form you came up with! And having something consistent for your population is a plus for anyone responding.

The biggest problem is keeping info up to date. I’m bad about that (and I know better!) I’m guessing you may end up having to remind people to update. Maybe quarterly?

Services like medicalert.org (available in many countries now) generally have the needed features to go with a bracelet or necklace, but at a price, which can get high.

I’m also seeing a push to have one’s info in a QR code stamped directly on the bracelet, etc. instead of the basics (blood type, allergies, major conditions.) Since I’m likely to be in trouble where there isn’t cell service that can read the QR, I find that disconcerting.

—

Phones can read QR codes just fine without cell connections. But since “most” QR codes are links to a site with more info, they won’t be able to go there. But then, the info behind the bracelet (or pendent) has previously been a phone call away, so…. -rc

A bigger problem than out-of-date forms is blank forms. We all have our own way of jogging memories for taking action, so somehow as your history changes it’s time to change your form.

Residents have discussed using QR codes, but I’m going old-fashioned and sticking with the paper taped to the inside of my closet door closest to my cabin door. My buddies will know where to find it.

Quite interesting. This topic has come to mind several times. I’m looking forward to the insurance post.

Will you be able to share the Life Raft form? Sounds like a lot of it would be helpful for landlubbers….

—

See my response to Tom. -rc

I am not yet a resident, but I would like to respond to the article addressing medical emergencies on board. Given that the average age of residents living on board is relatively high, it naturally leads to a higher risk of medical emergencies — a risk that will only increase with time.

There are certain medical emergencies that require immediate hospital care and cannot wait several hours for the ship to reach the nearest port. Allow me to give two frequent examples of such emergencies that necessitate prompt intervention.

During my medical studies (I am a physician), there was a phrase that summarized the management of myocardial infarction: “Time is muscle.” Similarly, in recent years, the same approach has been applied to the brain and strokes: “Time is neuron.” This understanding has led to the development of dedicated stroke units worldwide, ensuring that treatment can be provided ideally within three hours of onset. This has significantly reduced the mortality and long-term consequences of these conditions, just as with heart attacks.

Therefore, it seems evident to me that one should be able to rely, anywhere in the world, on the availability of helicopter rescue services. It is the responsibility of the ship’s company to maintain an up-to-date list of helicopters that can be contacted in case of emergency. It is also, of course, the responsibility of residents to have insurance coverage that includes air transport by helicopter.

If no helicopter rescue service is planned, every resident must be fully aware that by coming aboard, they are accepting the risk of not receiving medical care consistent with current standards. I am not a lawyer, but under these circumstances, I strongly recommend that the ship’s company ask every passenger and crew member living on board to sign a waiver to protect the company from potential legal action.

When the author of the article justifies the absence of a helicopter rescue service by stating that a stroke would have occurred anyway (whether on the ship or at home), and that those individuals might not necessarily have insurance or nearby hospitals available for treatment if they lived on land, I must respectfully disagree.

The company should be able to provide such a vital service, and it should be up to each person to decide whether they wish to have — and can afford — the means to benefit from it.

Living in Switzerland, where health insurance is mandatory and includes air rescue coverage, and where university medical centers are easily accessible, I am well aware that this issue also reflects a matter of culture.

However, would you willingly buy a car without airbags? It seems to me that beyond cultural differences, health is the most valuable asset we have, and every possible measure should be taken to ensure the safety and well-being of residents and crew members on board.

Pierre Porta MD

Switzerland

—

I look forward to having chats with you, Pierre. We are well aware of the Standard of Care for medical emergencies. I’m less aware of maritime law, but this is not a new problem: I expect ships are absolved of liability for medical emergencies that outstrip the care they can provide. Even a large ship (and this isn’t one) is very unlikely to have a cath lab to treat acute myocardial infarction (for lay readers: “heart attack”), let alone any real definitive care for a CVA (“stroke”). They can’t even stock tPA here (a miracle drug for ischemic (blood clot) strokes) as there is no imaging available onboard (CT/MRI) to rule out hemorrhagic (brain bleed) strokes.

Ships aren’t First World countries, and aren’t all that often near one. Helicopters save lives, and I’ve called them in numerous times to evacuate patients in the rural EMS system we worked in, but even when there is a chopper nearby, they can’t always respond: it’s not only a very limited resource, but there are other limits including altitude and weather (also a Swiss problem, eh?). If you’re expecting a chopper to fly an hour out to sea to evacuate a stroke off the coast of Africa, you will be disappointed.

I liken living here to living in a very rural area: resources are limited, and there’s a very real risk to being here. Last, we certainly did not “justify” the lack of a helicopter because “a stroke would have occurred anyway,” and that’s an offensive summary. Rather, it is a nod to reality: that the specific patient mentioned would have died even if there was a “stroke center” right aboard the ship, just as some AMI patients die despite the best EMS systems and nearby cath labs. We all will die sometime no matter how good nearby medical care is.

I will cover all of this and more in the next article. Indeed there are many vehicles we’ve already ridden in that don’t have seatbelts, let alone airbags. -rc

Pierre, I feel your frustration regarding the limits of onboard medical abilities. There are also hospitals on land that have limited facilities so patients must be transported to hospitals that have the requisite abilities.

The availability of helicopters isn’t up to the ship. We are dependent on not only the countries we are sailing near but also the weather. You must be aware of weather limitations on helicopter availability there in Switzerland.

This ship does a good job of caring for the residents, whether tending to them onboard or finding a hospital that will tend to them. This article is intended to be a reminder to do your homework before boarding, and to understand the limitations of the ship’s facilities. And, get the insurance that will suit your particular needs.

“Therefore, it seems evident to me that one should be able to rely, anywhere in the world, on the availability of helicopter rescue services.”

As a Brit, I think this is totally unrealistic. I’ve been on several cruises, mostly in the European area and I’ve certainly never expected that, if a medical emergency occurs, I will always be within range of helicopter evacuation.

This article and its comments highlight the need to be prepared for any emergency, whether on land or at sea. Despite years in the local volunteer fire service, I am often surprised by how little people plan for common incidents at home or in the community.

—

I came very close to losing a patient because we were delayed in arrival because they didn’t have their address posted at the top of their VERY long driveway on a rural dirt road, and I told them that. I begged them to post a big, clear, reflective number sign to speed things up “the next time,” especially since I might not be the one to respond. And you know what? They never did. -rc

Medicare parts B (and C) and D are optional and if you have them, you have to pay for them. (Medicare Part A is automatic but there is no charge for it.) Partial answer to the question about Medicare earlier.

Many folks take out a private Medicare supplement plan, which comes with premiums. My Medicare supplement requires that I carry Medicare part B, but it makes part D unnecessary and it also provides for care outside of the U.S. (Depending on the location, I might have to pay out of pocket and be reimbursed.) It will cover emergency transportation, but it won’t cover planned trips back to America for treatment.

I write all this as a means of mentioning the kinds of things one might want to keep in mind when considering what levels of Medicare, whether you’re first starting it or for the annual open season time to change plans. Also, things to think about while shopping for Medicare supplement plans.

Bill in Florida: It sounds like you may have a Medicare Advantage plan, not a Medicare Supplement. I say that because Advantage plans generally include drug coverage, where most, if not all, Supplement plans do not. There are a few Supplement plans that don’t include drug coverage, but they are designed for military veterans who have drug coverage with the government. If I were to sign up for one of those, I would be subject to a penalty for not having Part D.

I also know that some Advantage plans do include some international coverages, but I am not aware of any Supplement Plans that do.

—

And those which do provide foreign coverage probably have a limit to how long you can be gone, and/or how many days of the year. In other words, definitely not for months or years at a time. -rc

Along with this, do residents keep a “go bag”?

—

That is part of what Kit suggested when she outlined the Life Raft concept to Residents. -rc

Privacy onboard is so interesting to me. A cruise line just banned Google glasses. Which seems like something that should be banned everywhere as they pose a security risk along with furbies!

I’m kind of surprised that the ship doesn’t have its own helicopter on board for emergencies, but I guess it might be too expensive.

—

I’ve never heard of a chopper stationed on any cruise ship, even a gigantic commercial one with 6,000 passengers. Even if there was a place for it here (and on this tiny by comparison ship, there isn’t), I’d guess it would require every resident to pay $1,000-$2,000 extra per month to maintain a chopper and crew, which means doubling their monthly fees for a theoretical use once or twice a year, when we’re generally parked in port more than half the time. -rc